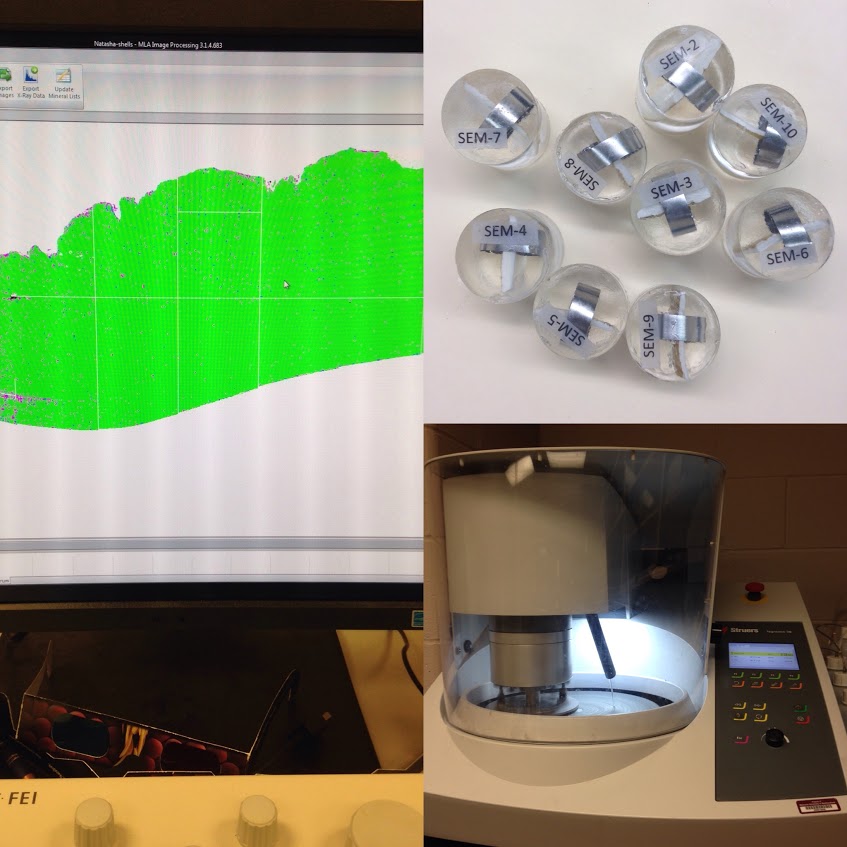

Since starting the New Year, I have been working on a collaborative and experimental project with my supervisor Dr. Meghan Burchell and Dr. David Grant at the Microanalysis Facility in Memorial’s Core Research Equipment & Instrument Training Network (CREAIT). For this project we are chemically and geologically examining live-collected butter clam shells from British Columbia with scanning electron microscopy and mineral liberation analysis to contribute to method development in the archaeological sciences.

All research projects start with an idea. The idea for this project came to me in the form of an email I received last semester at 5am from my supervisor. As a new student in the department, trying to make a good impression on my new supervisor, I of course sent back an enthusiastic “yes!” After we had completed the basic background research and had established the feasibility of the project, we started planning out the analytical work, which is potentially the most important step of the research process. I cannot stress enough how having a flexible research design is crucial when conducting experimental research. Especially when it is costing you money and time; you don’t want it all to go to waste. We had a best case scenario, a hypothesis that if confirmed could be ground-braking for the archaeological sciences, but we also built in the possibility of “failure” and how meaningful “failure” could be in its broader contributions to the field.

There is a general fear for graduate students that their research could “fail” and that they won’t be able to produce meaningful results. One of the most important lessons I have learned since starting grad school is that if you move to a positive space of mind a floodgate of possibilities starts to become visible to you; effectively eliminating the singular gloomy thought of “failure”. If you start thinking of “failure” as a learning and teachable experience then you will always be able to say something meaningful about your research.

The beauty of experimental work is that you’re doing something that nobody has ever done before. This gives you a lot of flexibility and many options on what to say about your results. However, doing unique research can be difficult when trying to make the technology work for your specific needs. Some of my colleagues in the archaeology department have joked about “just throwing ‘science’ at the data” to make sense of it, but first you need to understand the science and the equipment. This takes time and patience but can lead to fantastic rewards.

Dr. Grant first showed me how to work with the SEM in February, and within a couple hours I was doing it all alone…well, with the occasional look over my shoulder by Dylan Goudie, lab coordinator, who provided help when the software would inevitably crash #scienceproblems. This step of “teaching” and “doing” independently was repeated every time I came into the lab for the next research step and it allowed me to get in touch with all aspects of the research process. After a few complications in the scanning process we finally got the shells imaged and started analysing the information in depth. After quantifying the data, I had these beautiful graphs and spectra and had no idea what I was looking at. The great thing about collaborative work is that you don’t need to know everything, that’s why you have collaborators, each with their own skill sets to contribute. Dr. Grant and I have been working on image processing and analysing, and Dr. Burchell and I have been working on the interpretation and translation into archaeological terms.

With the Society of American Archaeology conference coming up soon, we are all rushing to have something meaningful to say about our data, but fear not World, our research design is failure-proof.

Until next time…

~Natasha